By Matt Cleary

It’s a warm, verging on a hot Friday morning at Accor Stadium and the dignitaries are fanning themselves with the event program and sweating in their suits. There are no complaints, though. Not today. For they’re here to honour a legend.

Chris Minns, the Premier of NSW, is here, with Jodie Harrison, Minister for Women, and Steve Kamper, Minister for Sport.

There’s David Gallop and Kerrie Mather, respectively chairman and chief of Venues NSW.

There’s Australia’s Olympic chief Matt Carroll and AOC President John Coates in a (wise) Panama hat.

Two-time Olympian Patrick Johnson is here. He once ran 9.93 for the hundred and remains Australia’s fastest-ever man.

Bruce McAvaney is here, too – he didn’t run for his country. But he could call sport for Australia.

And one famous Monday evening on September 25, 2000, he did, when upwards of 20 million eyeballs tuned in to see a famous hot lap of Stadium Australia.

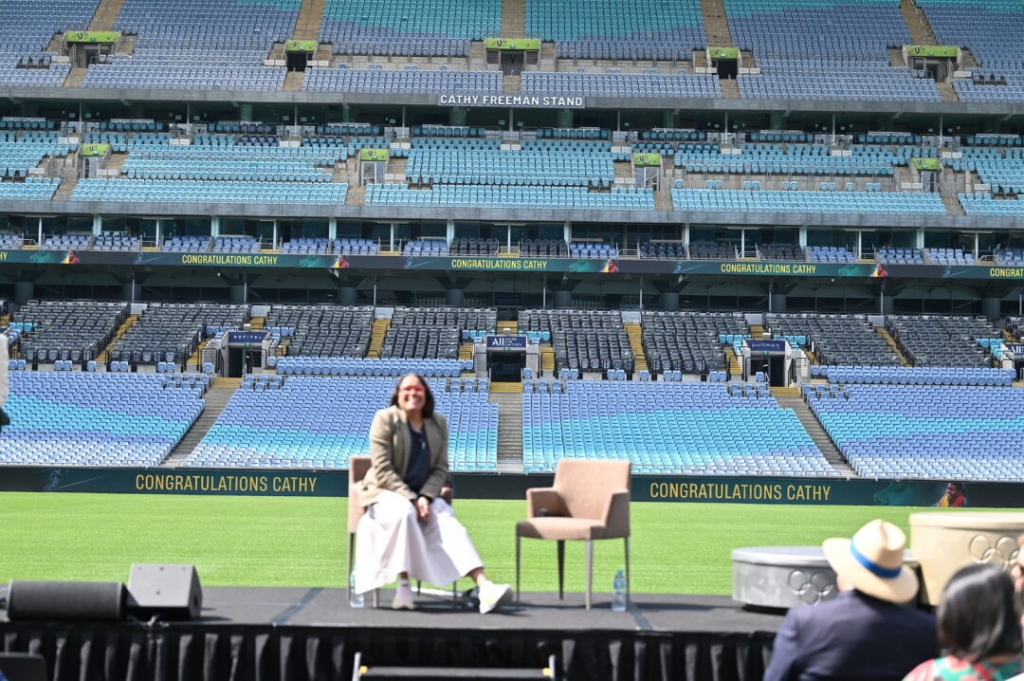

Such was – and remains – the pulling power of our guest of honour, Australia’s 400-metre Sydney 2000 Olympics champion Catherine Astrid Salome Freeman, OAM, who’s here with her family to witness the unveiling of the Cathy Freeman Stand on the eastern side of Accor Stadium.

Typically for Freeman, she’s a touch non-plussed at all the fuss.

“I’m just a Kuku Yalanji woman, a Birri Gubba woman, who’s just taking each stride, doing my best to be me, making the most of life and opportunities, drawing inspiration from my family, from stories, from learning along the way,” she tells interviewer and close friend, McAvaney.

“But this is such an incredible day today.

“I’m so honoured, I’m almost speechless.”

McAvaney assures her: “There won’t be a person in Australia that’s not smiling today, not one.”

There wasn’t one 23 years ago to the day when Freeman emerged in a fireproof white bodysuit to light the Olympic flame at the Sydney 2000 Opening Ceremony.

Ten days later, her win in the Olympic 400 metre final was the joyous pinnacle of the greatest feel-good fortnight Australia’s ever known.

Freeman’s dash today, like Shane Warne’s ‘Ball of the Century’, John Aloisi’s penalty goal and even Sam Kerr’s wonder strike against England, almost gets better with age.

Eyes turn to the Great Southern Screen, all 120 metres long of it, to watch a mash-up of vision of that famous race.

There are wide angles, close-ups, panoramas. McAvaney’s words are plastered 10 metres high across the screen.

And it’s like you’re back there watching afresh. Your arm hairs prickle. And you’re cheering her on: Go on Cathy. Go our girl.

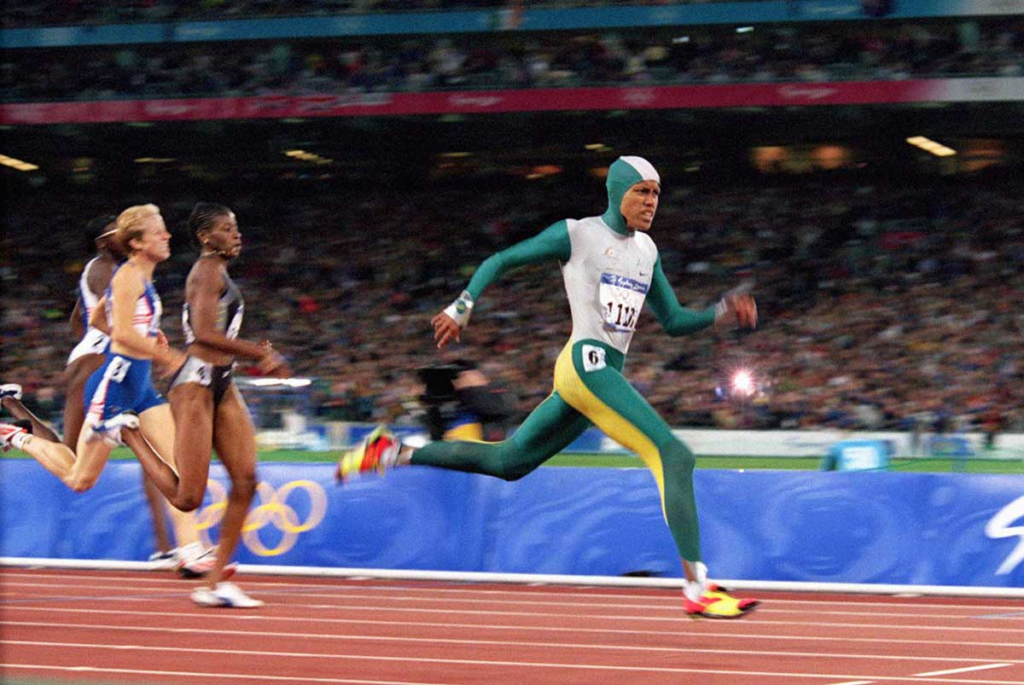

We see her shoot out the blocks, streaking around the track in that green-and-gold space-suit.

And there she goes, and she’s flying, leaning into the corners like a Ducati, equal parts pace, grace and power.

And you think: Man, she could move, Cathy Freeman. Her running style was beautiful. It seemed effortless.

It was the best in the world that fine night in Sydney, and we roared her home on the final turn and as she drew away in the last 40, 30, 20, 10 … gold.

You beauty.

It took effort, of course. That was plain to see after she’d crossed the line and sat on her bum on the track, the suit’s hood off her head, arms resting on her knees, breathing like a bellows, oxygen like balm for her lungs.

Soon enough, though, she was up and dancing about, waving the flags of her country and of her people, this shy country kid, beaming for Australia, for her mum and dad and family, for herself.

What a night. What a ride she took us on, so many years in the making.

As McAvaney explains on stage, since running second in Atlanta to arch-rival Marie-José Pérec – the Frenchwoman who fled Sydney after seeing building-sized posters of Freeman on the skyscrapers outside her Darling Harbour hotel room – Freeman won 43 of her 44 races, the one loss in Oslo in ’98 when she was injured.

She was all we could talk about. For four years we looked forward to the 400-metre final, Freeman versus Perec versus the world.

McAvaney asks about her confidence on the night.

“In terms of percentages, it was mainly confidence,” she replies. “But there was also that human component, a feeling of fragility, of self-doubt.

“Talking to Warwick on the way here – sorry, Warwick, our driver – you just don’t know what’s going to happen in big sporting moments. Those not expected to do well can do well. And vice versa.

“There’s a side that’s deep within. I said to my coach before I left him, will you still love me if I don’t win.

“There’s a duality.”

Then she emerged onto the arena where 112,000 people roared her name.

And she flicked the switch. She moved from Cathy the barefoot kid from housing commission in Mackay to Cathy Freeman: athlete; arse-kicker; animal.

She was in her realm.

“Once I got out there and I was in my element, as sports people are, and I’m at the start line … you just switch on and the competitive juices start flowing,” she tells McAvaney. “And you’re so determined and very clear on what you need to do.

“I won’t swear – but you get very aggressive.

“I was born to be an Olympic champion.”

And now, after a public process to name Australia’s greatest female athlete, the great state of NSW has named a great eastern stand after her.

Freeman is the first woman so-honoured in NSW.

Premier Minns tells media: “Everybody remembers where they were when Cathy Freeman produced her historic 400-metre race to win gold for Australia at the Sydney Olympics.

“I want the next generation of young girls to watch sport at this stadium, looking up at the Cathy Freeman Stand, thinking about their own sporting dreams.”